The Nature and Parameters of the Research Inquiry

This paper explores two broad questions: 1) Does the federal judiciary seek to impact or change duly passed congressional legislation and, 2) If so, how does the Congress react to these judicial initiatives. The underlying assertion is that key members of the judiciary attempt to deconstruct, rewrite or change congressional legislation, either for reasons of sound jurisprudence or because they personally disagree with Congress’s policies. This thesis is explored through a case study of a landmark Congressional Act, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA). Specifically, one section of the Act is the focus and is followed from its initial floor debate to final passage, implementation, and finally to judicial reaction.

Congress passed the IIRIRA, which was the most comprehensive immigration reform since the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. One key objective of the Act was to stop re-entry after deportation[1] by criminal aliens; that is, aliens who have been deported or removed on the basis of having committed a serious crime known as an aggravated felony. The Act expanded the definition and type of offense considered to be an aggravated felony and increased the severity of sanctions for re-entry by previously removed criminal aliens. An alien in removal proceedings who has been convicted of an aggravated felony on or after November 29, 1990, may be sentenced to up to 20 years[2] in prison for re-entry in violation of the removal order. This enhanced deterrent to illegal reentry is known as USC 1326, Section 2.

The Act, through the U.S. criminal code, names a significant number of crimes and classes of crimes considered to be aggravated felonies that could trigger 1326 incarceration sanctions. The list of crimes reads as follows:

[1] The term deportation was replaced by the term removal in the 1996 Act. There are some technical differences between the two terms but, for the purposes of simplicity, this paper uses the terms interchangeably unless otherwise noted.

In the years since the passage and implementation of the Act, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has rendered a significant number of decisions eliminating or weakening many of these crimes as a basis for removal in deportation hearings and for prosecuting criminal aliens for re-entry after removal. The result of this elimination has been to effectively deconstruct a portion of the landmark Act. A number of Ninth Circuit Court decisions seem to be, at least in part, based on the personal policy predilections of the judges rather than on jurisprudential considerations. There is evidence for this assertion. For instance, Ninth Circuit Judge Stephen Reinhart said in a debate with Circuit Judge Alex Kosinsky that he “sees the ‘little alien’ and ‘big government’ and is often inclined to favor the little alien.”[1] This may be a heartwarming sentiment, but it is not sound jurisprudence.

Through exploration of the Congressional Record, case law, interviews and other original sources, I establish that Congress passed valid immigration legislation to execute its specific intent to expand and strengthen laws directed at criminal aliens. Next, I establish that the executive legally and appropriately administered the new law and that the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals then began to deconstruct parts of the law. In the conclusion, I pose the question, “Does Congress attempt to defend its legislation from encroachment by the Court’s actions?”

Methodology

Primary research and source material comes from government records and from notes of personal interviews with judges, a congressman, and attorneys. These sources include an extensive review of the Congressional Record to establish the Congress’s intent when it passed the Act and the criminal alien re-entry sanctions portion of the Act. The review includes studying floor debates and extensions of remarks. I also rely on notes from my personal 1995 conversations with Congressman John Hofstettler of Indiana about his views on the immigration reform efforts of the 104th Congress (1995 – 1996). My description of group-illegal-entry in the form of “bonsai runs” is taken from newspaper accounts in the San Diego Union-Tribune and from my notes as an eyewitness.

Primary research on the early implementation and application of the “aggravated-felony-based deportation” section of the IIRIRA is taken from my notes of interviews with immigration judges, notes from conversations with the U.S Attorney for the Southern District of California during the mid-1990s, INS attorney interviews, interviews with the members of the immigration bar, and emails exchanged between these officials and me. Research on the response of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals is taken from reviews and accounts of circuit court opinions of appealed removal decisions rendered by immigration judges. I also rely on notes from my personal conversations with immigration judges regarding their efforts to administer the law in light of appellate court intervention. Additional information and data comes from think-tank accounts[2] of decisions by the Board of Immigration Appeals, as well as scholarly articles on the IIRIRA legislation.

A database of rhetorical comments by members of Congress was built from the Congressional Record. This database was created by first counting all rhetorical incidents of support and all rhetorical instances of opposition listed from search terms used in reviewing the Congressional Record for the 104th Congress. The result was 28 floor comments in support and 19 in opposition. This population of 47 remarks breaks down to 59% support and 41% in opposition. Not all 47 remarks could be included here as evidence. A sample of member remarks was randomly drawn from the population in a 3:2 ratio of supporting remarks (9) to opposing remarks (4). This allows the member comments included here to reasonably and accurately represent the total remarks made from the floor over the life cycle of the legislation.

In general, a descriptive, historical, and qualitative approach has been taken because it yields substantial information regarding legislative intent, executive action, and court response. The acquisition of data and information in these particular subject areas is achieved most readily by close examination of original documents and review of rhetorical records, rather than by strictly statistical measures and equation-based hypothesis testing. While a largely qualitative approach may introduce some subjectivity into the conclusions and revelations, it nevertheless provides insight and understanding into the multi-faceted and subjective area of Congressional-Court dynamics regarding judicial impact on valid legislation.

Literature Review

Research into the general area of the contemporary political relationship between the Congress and the Courts on criminal aliens is limited. Studies that do exist are found almost exclusively in the disciplines of social science and law and are from scholars writing in immigration journals or law reviews. Scholarly literature that is specifically focused on the 1996 Act, its application by the executive, and appellate court reaction is virtually non-existent. Research from the field of political science into specific causes and dynamics of the Ninth Circuit Court’s response to the IIRIRA does not exist. This paper will be the first.

One of the most recent authoritative pieces of literature on the general nature of Congressional – Court relationships is The Amorphous Relationship between Congress and the Courts by Michael A. Bailey, Forrest Maltzman, and Charles R. Shipman published in the Oxford Handbook of Congress. Michael A. Bailey is the Colonel William J. Walsh Professor of American Government in the Department of Government at Georgetown University and teaches at the McCourt School of Public Policy there. Forrest Maltzman is a professor of political science at Georgetown University. Charles R. Shipman is the Ira and Nicki Harris Professor of Social Science at the University of Michigan, where he holds appointments in the Department of Political Science and the Ford School of Public Policy.

Isabel Medina did the only scholarly work that mentions the narrow area of the aggravated felony portion in the IIRIRA. Her work titled “Judicial Review – A Nice Thing – Article III – Separation of Powers and Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996” addresses the effort by the INS and DOJ to get Congress to eliminate Article III Courts from reviewing their agency decisions. Medina includes a brief reference to the aggravated felony provisions of the Act.

Austin T. Fragomen, Jr., presents an analysis of the legal impact of the new law on various classes of foreign nationals in the United States. His article “Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996: An Overview” was published in The International Migration Review in the summer of 1997.[3] Lina Newton, Associate Professor of Political Science at Hunter College, has written about the field of immigration reform publishing a scholarly book, Illegal, Alien, or Immigrant: The Politics of Immigration Reform (2008). Newton’s book is a critique of immigration policy as nativist and implies that there is more than a little irrationality and prejudice behind policies that restrict open entry into the country. She expresses her views with authority and factual support and makes vivid arguments despite her significant tilt toward open borders and loosely restricted entry.

While these works direct themselves toward the issue of immigration reform and congressional action in general, they do not explicitly explore the relationship between Congressional legislation and the Court’s response to that legislation. As a result, the political and legal relationship between Congress and the Courts is an inviting area for additional research and inquiry. A body of literature on this general relationship could form the foundation for more narrowly tailored research on specific pieces of legislation and court challenges to them.

The 104th Congress’ Intent with Regard to the Removal of Criminal Aliens

Exploring and establishing Congressional intent behind the aggravated felony provision of the IIRIRA is the first step toward understanding what happened in the courts in the years after passage. The bill was created, debated, and passed by the 104th Congress. Illegal entry into the United States had been a growing issue since the so-called “bonsai runs” of 1992 and 1993. Hundreds of foreign nationals would gather on the Mexican border at the head of Interest Highway 5 in San Ysidro, California.[4] On a given signal, as many as 500 would charge the American border, running down I-5, overwhelming the border patrol and thereby successfully entering the country in violation of law and without inspection.[5] According to the San Diego Union-Tribune, hordes of immigrants regularly stormed the border, startling and endangering drivers on I-5.[6] These bonsai runs would spontaneously arise and occurred frequently, thus creating public concern.

A number of illegal entrants gaining entry through these bonsai charges later committed serious, often violent, crimes against American citizens. A House Judiciary Committee report on the history of illegal immigration released on May 22, 2014, by Chairman Bob Goodlate reveals that of the 35,318 criminal aliens released between 1994 and 1999, 37% had been convicted of another crime in the United States by 2000.[7] Their crimes ranged from burglary to rape to murder. These criminals would serve time in prison then be deported back to their country of origin. However, they would promptly and repeatedly return to the United States in violation of their removal orders then commit additional crimes. Before the 1996 Act, they faced little or no legal sanction for violation of their removal orders and, therefore, continued to repeatedly re-enter the country in violation of deportation orders. Large-scale illegal entry in general, and re-entry by criminal aliens in particular, became a serious issue and area of political interest.

Given this environment, several members of Congress responded by making illegal entry in general and criminal aliens in particular a campaign issue. The 104th Congress reacted by passing the Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act that included expanding the aggravated felony law to include an extensive list of serious crimes that could be used to trigger deportation based on criminal conviction.[8] The Congressional Record for the 104th Congress reports floor debates and extensions of remarks that reveal the intent behind the new aggravated felony law. Floor debates often become mired in arcane discussions of rules and procedure. It is the rhetoric in the extension of remarks in which one finds a more direct and open professing of intent by legislators. Therefore, this paper primarily explores the extension of remarks portion of the Congressional Record to establish intent.

The bill’s sponsor, Texas Congressman Lamar Smith, introduced the 1996 Immigration Act, also known as HR 2202, on August 4, 1995.[9] The bill had 129 bi-partisan co-sponsors.[10] Such significant levels of co-sponsorship indicate an institutional predilection toward an intent to support the general premise behind a bill in consideration. As Krutz (2005) notes, the likelihood that a measure receives serious attention is reflected in the number of legislators that endorse the measure through co-sponsorship. [11] Given this widespread endorsement through co-sponsorship, it is likely that the intent of Congress as an institution will be reflected in the floor remarks of individual members.[12]

Mr. Smith, while speaking to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of Union on Friday, February 10, 1995, said, “An increasing amount of crime is being committed by non-citizens: both legal and illegal aliens. About 25 percent of all Federal prisoners are foreign born. An astounding 42 percent of all Federal prisoners in my State of Texas are foreign born. Recidivism rates for criminal aliens are high – a recent GAO study revealed that 77% of noncitizens convicted of felonies go on to be arrested at least one more time.” He continues his address to the Committee of the Whole House with, “The Bureau of Prisons estimates that over 75% of noncitizen inmates are confined for drug law violations… Because of the porous nature of our border, drug traffickers who are deported…come back across the border into the United States.”

In another section of the Congressional Record for the 104th Congress, Mr. Smith says, “The Criminal Alien Improvements Act of 1995[13] further expedites the deportation of criminals after they have served their sentences…this bill increases the list of aggravated felonies for which an alien can be deported as criminal aliens.” Congressman Smith lays out the intention of the legislation as being generally directed at preventing repeat crime by previously deported criminal aliens. This expressed intent connects directly with the public’s concern over illegal entry and the “bonsai runs” of the early 1990s. The intent revealed in the record can be seen as an attempt to deliver on campaign promises to stop illegal re-entry, especially by previously removed criminal aliens.

Several co-sponsors of the IIRIRA are in the Congressional Record speaking about the problem of criminal aliens re-entering the country. The concern expressed from the floor was often related to the re-entry of criminal aliens almost immediately after their receiving a removal order from an immigration judge. Congressman C.W. Bill Young rose to speak on February 10, 1995, to address the issue of illegal alien crime. He said, “The legislation we consider today makes several amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act and other immigration laws to address the problem of aliens who commit serious crimes while they are in the United States…[this] give[s] federal law enforcement officials additional tools with which to combat…immigration [related] crime.”[14]

Congressman Randy Tate rose to speak on January 25, 1996, in favor of the IIRIRA. He said, “The Immigration and Naturalization Service estimates that 300,000 people enter the United States illegally every year, and 3.8 million currently live in this country illegally.[15] These people are taking advantage of American generosity and openness without regard for our laws or principles…[This] is at the expense of those [legal entrants] who choose to play by the rules and come to America legally. I am supporting legislation to end this madness. Mr. Speaker, I urge my colleagues to support this legislation and to stand up for integrity.”[16] Later in the 95-96 session, Congressman Hyde spoke in favor of the new immigration law on March 19, 1996. He said, “…immigration reform is one of the most important legislative priorities facing the 104th Congress. Today, undocumented aliens surreptitiously cross our border with impunity….The 104th Congress can make an unprecedented contribution to the prevention of illegal immigration as long as we have the will to act. H.R. 2202 provides for…greater deterrence to immigration related crime…and expeditious removal of persons not legally present in the United States.”[17] During another floor debate, Congressman Gallegy rose in support of HR 2202 by saying, “The primary responsibilities of any sovereign nation are the protection of its borders and the enforcement of its laws. America is a nation of immigrants…and at its core celebrates legal immigration.”[18] Congressman Julian Dixon spoke on January 5, 1996, saying, “…one of the most important changes in INS procedures was…the decision to expand and accelerate the procedure for holding formal deportation hearings …for those who had served time on criminal convictions.”[19]

Near the end of the debate on the IIRIRA, Congressman Bill McCullum of Florida rose to speak on the issue of adjudication of deportation matters. He said, “I believe it is time…to establish a full-blown adjudicatory system in statute [for immigration hearings].” Mr. McCullum’s objective, albeit unsuccessful, was to include amendments moving the Immigration Court from agency supervision and management to Article I status. [20]

Member commentary in the Congressional Record supports a conclusion that Congress intended to inhibit re-entry of criminal aliens who are deported on the basis that they were convicted of serious crimes known as aggravated felonies. The product of that intent was USC 1326, Subtitle B – Criminal Alien Provisions, Section. 321 through Section 324 (penalty for reentry of deported aliens). The subtitle and these sections were part of the Conference Report on H.R. 2202 that was passed and became popularly referred to as the IIRIRA.

Despite the wide support for the IIRIRA and an intention to expand sanctions against illegal re-entry, the Congressional Record also reveals opposition to significant portions of the bill. In fact, as mentioned in the section on methodology, 41% of member floor comments spoke in opposition to certain sections of the proposed legislation. Congresswoman Maxine Waters rose to speak on March 26, 1996, saying, “I am well aware of many of the problems and economic concerns with illegal immigration. H.R. 2202 is an extreme measure that not only attempts to stop illegals from crossing our borders—often in unworkable and repressive ways—but also limits many…family members from joining us in America. I support securing our borders with more agents, better equipment, and sturdy barriers…but I vote no as to final passage.”

More opposition was expressed by Congressman Chrysler, who rose on March 20, 1996, to speak on the Chrysler-Berman amendment[21] by saying, “It is simply wrong that this immigration reform bill prohibits adult children…from immigrating to the United States. That’s right. Under this bill no American citizen will be able to apply for a visa for their close family members…Mr. Chairman, in a country of 260 million people, 700,000 legal immigrants is not an exorbitant amount. We are all immigrants and descendants of immigrants…”[22]

Next, Congress Berman spoke in opposition to the bill and in favor of his amendment by saying, “Mr. Chairman this debate is really about one’s vision of America. I think it is fundamentally wrong to take the justifiable anger about our failure to deal with the issue of illegal immigration and piggyback on top of that anger a drastic…40 percent cut in permanent legal immigration. Preserve the existing system. Do not tear it apart.”[23]

All of these remarks for and against various elements of the Act reveal a significant fact regarding the congressional intent behind the passage of the criminal alien re-entry portion of the law. The varying arguments and remarks on H.R. 2202 (IIRIRA) share a common trait: None of them oppose the section tightening the sanctions on criminal aliens who re-enter in violation of their removal order. The intent of Congress with regard to criminal alien removal based on an expanded list of aggravated felonies was clear: Tougher penalties for subsequent re-entry was an area of total agreement. The next step in understanding what happened to the IIRIRA and its aggravated felony provision after passage is to examine how the executive applied the act in the years immediately after passage.

Application and Implementation of the IIRIRA and USC 1326

Congress expressed a clear and unambiguous intent to strengthen and expand sanctions against criminal aliens who had committed serious crimes against United States citizens. After passage of the Act, the Department of Justice and Immigration and Naturalization Service[24] became responsible for promulgating rules and regulation and for administering criminal alien removal. During the first few months, deportation based on conviction for an aggravated felony and prosecution for re-entry in violation of that deportation order was unencumbered by appellate court decisions. The law was working largely as intended by Congress.

The Immigration Courts[25] were mindful of possible challenges to deportation orders that had been based on aggravated felonies. They took significant steps to secure their decisions against constitutional challenge. Given the severe sentences for those convicted of re-entry on the basis of a removal order, criminal alien respondents were afforded enhanced due process at their removal hearing in Immigration Court. The Immigration Courts held training conferences to instruct judges in the adjudication of removal cases under the Act.[26] Specific guidelines were provided that compelled notification requirements when a removal order was based on the newly expanded aggravated felony provisions. Each respondent who was issued a removal order based on the commission of an aggravated felony was to be given on-the-record advisals that illegal re-entry carried the possibility of long prison sentences. Immigration judges, as a matter of procedure in each hearing, began issuing these advisals to ensure due process notification of the consequences for violating the order.

United States Attorneys were provided tight guidelines for the prosecution of cases involving illegal re-entry after deportation by criminal aliens. These activities demonstrated that the 104th Congress had operationalized its intent to remove criminal aliens and stop their illegal re-entry. It had not equivocated. USC 1326 stated, “[A removed alien] whose removal was subsequent to a conviction for commission of an aggravated felony, such alien shall be…imprisoned for not more than 20 years.”

The IIRIRA went into effect on September 30, 1996, with the Immigration Courts seeing the first removal hearings based on the commission of aggravated felonies in the last three months of 1996. In early 1997, the U.S. Attorney’s Office began to criminally prosecute its first illegal re-entry cases under the new law. By early 1999, the first cases challenging immigration judges’ orders removing criminal aliens were decided by appellate courts. Courts also begin responding to challenges to U.S. Attorney 1326 criminal re-entry prosecutions.

Many—perhaps most—immigration lawyers specialize in defending aliens who are in deportation or removal proceedings before the United States Immigration Court. Aliens in deportation and removal proceedings are in civil, not criminal, proceedings. The civil penalty for illegal presence is removal. These aliens usually acquire illegal status by entering without inspection, attempting to enter with false papers, or overstaying a temporary legal status. If these aliens are deported, they are prohibited from legal entry for five years. If during these five years they re-enter in violation of the order, they face criminal prosecution and up to one year incarceration for re-entry although U.S. Attorneys rarely charge them. Instead, the U.S. Attorney simply lets the violator face another removal proceeding in Immigration Court. Under the IIRIRA, those aliens who were removed for illegal presence and who also were convicted of an aggravated felony while present face additional sanctions, including up to 20 years in prison. Immigration judges were removing criminal aliens and U.S. Attorneys were prosecuting these criminal aliens for re-entry, just as Congress had intended under the new aggravated felony provision. This is a classic example of how the American government is designed to function. An issue of public concern had arisen; that is, the illegal entry and commission of violent crimes. Congress responded with campaign promises, debate, and legislation. The executive was implementing the law as intended by Congress. However, this functioning was derailed, at least partially, by the decisions and opinions of judges in the federal courts, most particularly the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Depending on how one views the evidence, this derailing was either appropriate jurisprudential intervention based on constitutional considerations or inappropriate judicial activism meant to engineer social norms.

The 9th Circuit and Others Respond to Congressional Intent Expressed in IIRIRA 1996

The Ninth Circuit’s dislike of Congress’s enhanced criminal alien sanctions quickly arose. This dislike is in harmony with several of the criticisms launched from the legal academic community. Together, academics and the Ninth Circuit began to form the nucleus of a reactionary response to the new law. Nancy Morawetz, when writing in the Harvard Law Review, opined that, “…with regard to deportability and eligibility for relief,[27] the most publicized aspect of the new laws is their Alice-In-Wonderland-like definition of aggravated felony.”[28] The essay argues that the effort to develop a per se list of offenses that mandate deportation is fundamentally misguided.”[29] Morawetz and others criticize those circuits that uphold Congressional intent of the law while embracing the one circuit that unwinds the law. She writes, “…the Third Circuit has held that a conviction for the…crime of petty theft under New York law with a one year sentence constitutes an aggravated felony under the immigration laws.”[30] Few criticisms of the Ninth Circuit decisions striking or limiting the new law can be found prior to 2002. One cannot say for sure if the Court is taking cues from legal academics, but their respective themes converge quite nicely and the correlation is noteworthy. In a 2002 case before the Circuit, a native of Guatemala pled guilty to two separate second-degree commercial burglary charges. Homeland Security issued a Notice To Appear,[31] thereby commencing removal proceedings. The court decided that this burglary was not an aggravated felony by commenting that “…entering a commercial building with the intent to steal items therein was not, as a matter of law, a ‘substantial step’ supporting conviction for attempted theft.”[32]

In another case, Chavez-Solis v Lynch in 2015, the panel could not seem to find possession of child pornography an aggravated felony. In 2011, after pleading nolo contendere to charges of possessing child pornography in violation of California’s penal code, Mr. Chavez-Solis was sentenced to 150 days imprisonment. Subsequently, the Department of Homeland Security charged him with removability as an alien convicted of an aggravated felony. But the Court determined that his conviction did not qualify as an aggravated felony. Their decision was based on what they said was the California law’s vagueness and overly broad construction.

The Ninth Circuit is not the only appellate body that is inclined to free convicted criminal aliens from the shackles of the aggravated felony designation. The Board of Immigration Appeals, which is the first level of appeal from deportation and removal orders, almost immediately begins to make decisions reversing Immigration Court applications of the aggravated felony provision. Board Members Cecilia Esponza, Lorry D. Rosenburg, and Gustavo Villageliu concluded that “…appellant Melanie Beaucejur-Jean’s crime “does not constitute a crime of violence and is not an aggravated felony subject to deportation guidelines.” And what was Beaucejur-Jean’s crime that these three said did not constitute a crime of violence? Beaucejour-Jean had been convicted in upstate New York of killing an 18-month-old baby in her care. “I hit him two or three times with my fist on the top of his head. I did this to stop him from crying. It did not work. I do not know how long I shook him but I did not stop until he was unconscious.”[33] The Center for Immigration Studies wryly observes, “Beaucejour-Jean was ordered deported as a criminal alien but, thanks to this trio of ‘it’s-not-over-till-the-alien-wins’[34] appellate reviewers, Beaucejour-Jean remained in America.” In light of this startling decision, one might ask if the Board of Immigration Appeals reviewers are deciding legal matters according to personal political views rather than on proper jurisprudence. The Center for Immigration Studies suggests that a partial answer might lie in the fact that Board Member Espinosa named her son after the violent Marxist guerilla Che Guevara.

Another recent Ninth Circuit case, Lopez-Valencia v Lynch, 2015, continues to narrow the scope of the new law. In this case, Judge Margaret McKeown writes, “The central issue in this appeal is whether a conviction under California’s theft statute may qualify as an aggravated felony.” She goes on, “We hold that a California conviction for theft is never an aggravated felony because it is categorically not a theft offense.”

Curiously, Ninth Circuit en banc decisions seem to differ from their three-judge panel decisions, lending evidence to support the conclusion that the attacks on the aggravated felony provision are coming from an ideological faction on the Court rather than from the whole Court. We see this in Randhawa v Ashcroft 2002. In this case, Sonny Randhawa was issued a Notice To Appear by the INS and placed in deportation proceedings in Immigration Court where he was ordered deported as an aggravated felon. On appeal, he argues that his conviction for stolen mail is not an aggravated felony under 8 USC §1101(a)(43)(G). The en banc panel disagreed and upheld the conviction as an aggravated felony. Other cases decided en banc upheld the aggravated felony enhancements. For instance, in Estrada-Rodiquez v Mukasey, the court said, “…we hold that resisting arrest under Arizona Revised Statutes § 13-2508 is categorically an aggravated felony…” There appears to be a faction on the Circuit attacking the application of the aggravated felony provision.

Law is complicated, technical, and often less than apparent. The cited cases may be rightly decided as matter of statutory construction or constitutional principle. On the other hand, the cases may represent judicial activism and social engineering by the court. This paper does not answer the question one-way or the other. The question posed here is: Was there a negative court impact on the aggravated felony-enhancement legislation that was validly passed by Congress in 1996? The above-cited cases say yes. Katherine Brady of the Immigration Resource Center (IRC) provides the most accurate description of court impact. Her job with the IRC is to instruct immigration lawyers on how to defend cases against aliens in deportation and removal proceedings, including those aliens deportable as aggravated felons. She tells lawyers, “If you represent an immigrant convicted of a crime…relying on older precedent you may think that the conviction [for an aggravated felony] has adverse immigration consequences, when under recent precedent it should have no consequences, or at the very least less serious consequences.”[35] What more eloquent revelation can there be to prove that the courts have deconstructed Congress’ aggravated felony portion of the IIRIRA?

I suggest that the evidence presented here leaves no doubt that Congress’ intent, in the instance of the aggravated felony provision of the IIRIRA, has been significantly “undone” by the courts. Determining whether this undoing was the result of sound jurisprudence or political activism is beyond the scope of this paper and legal expertise of the writer. The questions asked here are what, if any, was the response of Congress? What should be Congress’ response?

Congress Fails to Respond to Court Deconstruction of the Aggravated Felony Provision

As the evidence here indicates, decisions from the Courts and the Board of Immigration Appeals began to reverse or remand immigration judge removal decisions based on conviction for aggravated felonies. U.S. Attorneys trying to prosecute criminal aliens for re-entry met a similar appellate fate. Federal District Courts failed to follow the sentencing parameters in the Act. Instead, they most often sentenced to time served, amounting to a few weeks or few months. One reasonable conclusion is that many federal judges simply disagreed with Congress and were attempting to piecemeal deconstruct the legislation.

This poses the question: Would Congress drop the other constitutional shoe and pass additional legislation to counter court deconstruction of the aggravated felony provision? Congress had a number of options available. Many of the court decisions were based on the vagueness of state criminal law, rather than on the IIRIRA law in chief. Congress could have added amendments that addressed this problem. For instance, it could have instituted requirements for states to clarify the pertinent sections of their criminal code or lose federal law enforcement assistance. This political tool has long been used by Congress to influence state legislatures in other areas, such as social services or education policy. However, the Congressional Record shows that no such legislation was passed and floor remarks were few.

Congress could have re-written parts of the aggravated felony provision to eliminate any doubt about what it intended to be an aggravated felony. Statutes are often little more than general guidelines that leave the details to be specified by agency rules and regulations. This was decidedly not the case with the IIRIRA, as the definition of aggravated felony was unusually specific to the extent that it even provided a chart of offenses. Nevertheless, federal judges, if they dislike the policy objectives of a given statute, seem willing to deconstruct any part of the statute they can deem vague.[36] Congress can always counter this judicial action with tighter, more specific legislative language. But no such congressional action is revealed in the Congressional Records for the 105th through the 114th Congresses. Congress has become inert when it comes to responding with changed criminal alien legislation.

However, by the 108th Congress we see the return of rhetoric, if not substantive legislation, aimed at criminal aliens and illegal immigration. On September 21, 2004, House members traded remarks about the continuing problem of illegal immigration, especially by criminals. We heard a member rise and state, “In any event, the numbers suggest that tens of thousands of criminals, quite possibly hundreds of thousands, treat the southern border as a revolving door to crimes of opportunity. The situation is so out of control that 400,000 illegal aliens who have been ordered to be deported, 80,000 have criminal records—and the agency in charge, the Department of Homeland Security, does not have a clue to the whereabouts of any of them…” On the same day, another member rose to say, “Perhaps the most alarming aspect of having 15 million illegals at large in society is Congress’s failure to insist that federal agencies separate those who pose a threat from those who don’t. The open borders, for example, allow illegals to come into the country, commit crimes and return home with little fear of arrest or punishment.”

The Congressional rhetoric from the House floor continued in the 109th Congress. Congressman Sensebrenner, speaking to his colleagues on December 15, 2005, during a debate on the Border Protection, Antiterrorism, and Illegal Immigration and Control Act of 2005, tells his colleagues, “Our nation has lost control of its borders, which has resulted in a sharp increase in illegal immigration and has left us vulnerable to infiltration by terrorists and criminals. Estimates indicate that there are currently more than 10 million illegal aliens already here and that figure grows by a half million each year.”

It is déjà vu all over again. The floor remarks go on, as if IIRIRA had never been passed. There is, however, a new aspect included in Congressional discussion and that is terrorism. New immigration bills are introduced in both the 108th and 109th Congresses. The term “comprehensive immigration reform” enters the congressional lexicon and the public conscience. The key event since the passage of the IIRIRA was the 9/11 attacks on the nation. Even with this world-changing event, Congress cannot seem to pass its so-called comprehensive immigration reform. Throughout these congressional discussions on illegal entry, the aggravated felony provision regarding re-entry of criminal aliens fades from discussion. However, with the 2015 decision in the Chavez-Solis v Lynch, deconstruction of the provision continues. Congress’s only response found in the Congressional Record is a rhetorical whisper.

Conclusion

This paper began by posing two general questions: 1) Does the federal judiciary, on its own volition and initiative, seek to impact or change duly passed congressional legislation and, 2) If so, how does Congress react to these judicial initiatives? The case study that is presented provides evidence that the answer to the first question is yes. The federal judiciary, particularly in the form of Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decisions, does impact and change the law.

The evidence suggests that this impact and change may be driven as much by the Circuit judges’ and Board of Immigration Appeals’ own policy opinions and personal ideology as by sound jurisprudential consideration. This evidence is found in the impact, nature, and language of the decisions reversing or remanding many immigration judge orders of removal that were based on the aggravated felony law. More evidence is offered in the public debates between the judges during which at least one readily and proudly admits to favoring one party over the other based on extra-judicial considerations. Still more evidence can be found in the correlation between law review articles that are critical of the aggravated felony provision and court decisions. My interviews with immigration judges revealed their frustration at trying to follow the clear meaning of the statute, only to be reversed or remanded by the circuit court. My conversation with Congressman Hostettler indicated that members of Congress sought to pass straightforward legislation expanding and enhancing criminal alien sanctions. According to the Congressman, the legislation was intended to increase public safety and address national security vulnerabilities. Mark Reed, District Director of the Immigration and Naturalization Service in Southern California from 1992 to 1996, told me in some detail why criminal aliens presented a clear and present danger to the country and why the aggravated felony provision would help ameliorate these dangers. Alan Bersin, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of California, met with me throughout 1995 and 1996 to express his concern over criminal alien activity and the need to use the aggravated felony provision to stem criminal activity.

Despite these all these factual indications of danger to public safety and national security, despite Congress’s clear expression of intent through legislation, and despite the Immigration Court’s considerable efforts to ensure due process, the Ninth Circuit, or at least a large faction of it, saw fit to begin deconstructing the aggravated felony law.

In the end, Congress failed to respond with anything other than short-term rhetoric. It did not challenge the judiciary with additional legislation. There is a legitimate constitutional question here: Do the Courts attempt to change Congressional policy with which they disagree by deliberately fashioning decisions that unwind Congressional decision-making? If they do, where is the Congres

[1] Ninth Circuit Judge speaking to immigration judges at conference

[2] Primarily accounts written by The Center for Immigration Studies.

[3] The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996: An Overview Austin T. Fragomen,

Jr., The International Migration Review Vol. 31, No. 2 (Summer, 1997), pp. 438-460 Mr. Fragomen, Jr., is

Chairman of the global law firm of Fragomen, Del Rey, Bernsen & Loewy LLP and chairman of the American

Council on International Personnel.

[4] Congressional Record, Volume 142, Issue 40.

[5] http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/program.pl?ID=343211

[6] San Diego Union-Tribune, August 8, 2015.

[7] House Judiciary Report on Criminal Alien Crime and Recidivism, released May 22, 2014.

[8] See list-of-crimes chart on page 2 of this paper.

[9] Congressional Record of 104th Congress , search terms Lamar Smith + Immigration + IIRIRA.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Networks in the Legislative Arena: How Group Dynamics Affect Co-sponsorship, Kathleen A. Bratton

Department of Political Science Louisiana State University.

[12] Ibid.

[13] A sub part of the general 1995-1996 legislative package on immigration reform and illegal re-entry.

[14] Congressional Record of the 104th Congress, Extended Remarks, February 10, 1995.

[15] In the 19 years since these statistics were compiled, near abandonment of border enforcement has resulted in a loss of accurate data but estimates of currently-present illegal aliens is between 11 million and 20 million.

[16] Congressional Record of the 104th Congress, extended Remarks, January 25, 1996.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid, January 5, 1996.

[20] Article I status would remove the court from direct agency control and establish it as an independent administrative court whose decisions are not subject to agency review but appealed directly to the federal judiciary.

[21] The amendment sought to expand family unity requirements.

[22] Congressional Record, Floor Debate, March 21, 1996.

[23] Ibid.

[24] On November 5, 2002, the Immigration and Naturalization Service was renamed and subsumed into the Department of

Homeland Security.

[25] The Immigration Courts are under the jurisdiction of the Executive office for Immigration

Review in the Justice Department.

[26] 1997 Immigration Judge’s Training Conference, Schedule of Break Out Sessions, Executive Office for

Immigration Review.

[27] Virtually all respondents in removal or deportation proceedings admit and concede illegal presence and deportability. They are litigating a claim that they are eligible to qualify for relief (a legal excuse) from deportation.

[27] Nancy Morawetz, Harvard Law Review, Vol. 113, No. 8 (Jun., 2000), pp. 1936-1962.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Title of the formal charging document used by ICE to bring illegal presence charges.

[32] Hacking Law Firm, website on immigration law at www.hackinglawfirm.com.

[33] Transcript of interrogation of Beaucejur-Jean by the Monroe County (New York) Sheriff’s Office.

[34] A comment by the writer for the Center for Immigration Studies that is often repeated in the environment of immigration law enforcement.

[35]Kathy Brady is Director of IRC and graduated from Stanford University and Boalt Hall School of Law. She taught immigration law as an adjunct professor at Santa Clara University and New College School of Law and supervised students at the Stanford University Law School Immigration Clinic.

[36] An example is Judge Dolly Gee’s court orders on bond and legal representation of detained aliens.

[2] See United States Code 1326, Section 2, (d).

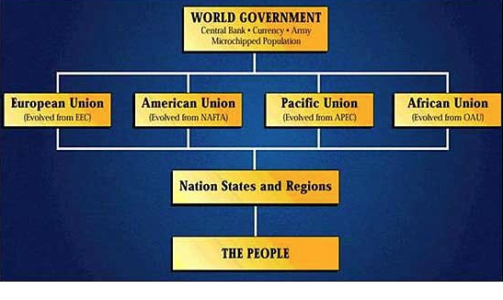

Take for instance Chief Justice John Roberts. Evidence reveals that Justice Roberts is, in all likelihood, a Deep State operative and main-player in the current insurrection to seize-back control of the United States government. Roberts’s being married to far-left Democrat Party political operative Mary McCord and his good-friends relationship with fellow Deep-Stater Norm Eisen should alert everyone that the Chief Justice is about to use his vote on the Court to play politics and destabilize the Executive Branch of the government. That’s just for starters. Biden-appointed Justice Katanji Brown-Jackson is a law-flaunting, Democrat Party political goon with seemingly no allegiance to the United States Constitution despite having sworn to protect it. The oath apparently means nothing to her. Then we have Sonia Sotomayor who famously said that she would rely on her “personal life-experience as a Latino Woman” in making Supreme Court decisions, writing opinions, and issuing injunctions. Apparently, the canons of Anglo-American jurisprudence and the rule of law are mere asides to Justice Sotomayor. Then we have the Bush-appointed Justice Elena Kegan whose idea of the law is to use it as means to establish her dimly thought-out radical progressive cultural vision. Then there is Justice Amy Coney Barrett who, at the recent State of the Union speech by the President, seems to exhibit a searing hatred of the man who appointed her. The only true Constitution-adhering Justice seems to be Justice Clarence Thomas. The remaining Justices are wild cards to say the least. The federal judiciary is mostly a cabal of globalist Democrat Party sycophants. God help us all.

Take for instance Chief Justice John Roberts. Evidence reveals that Justice Roberts is, in all likelihood, a Deep State operative and main-player in the current insurrection to seize-back control of the United States government. Roberts’s being married to far-left Democrat Party political operative Mary McCord and his good-friends relationship with fellow Deep-Stater Norm Eisen should alert everyone that the Chief Justice is about to use his vote on the Court to play politics and destabilize the Executive Branch of the government. That’s just for starters. Biden-appointed Justice Katanji Brown-Jackson is a law-flaunting, Democrat Party political goon with seemingly no allegiance to the United States Constitution despite having sworn to protect it. The oath apparently means nothing to her. Then we have Sonia Sotomayor who famously said that she would rely on her “personal life-experience as a Latino Woman” in making Supreme Court decisions, writing opinions, and issuing injunctions. Apparently, the canons of Anglo-American jurisprudence and the rule of law are mere asides to Justice Sotomayor. Then we have the Bush-appointed Justice Elena Kegan whose idea of the law is to use it as means to establish her dimly thought-out radical progressive cultural vision. Then there is Justice Amy Coney Barrett who, at the recent State of the Union speech by the President, seems to exhibit a searing hatred of the man who appointed her. The only true Constitution-adhering Justice seems to be Justice Clarence Thomas. The remaining Justices are wild cards to say the least. The federal judiciary is mostly a cabal of globalist Democrat Party sycophants. God help us all.

Thus it was, that the rule of law, Anglo-American jurisprudence, the American Constitution and Western democracy instantly disappeared in flurry of edicts, kangaroo courts, and declarations of absolute power by bureaucrats and politicians around the world. These self-declared all-powerful self-adoring elites acted as one, worked in unison, and moved into action simultaneously. The citizens of the West were, in one fell-swoop, transformed from free and independent citizens into political slaves and prisoners. This state of affairs continued until the Spring of 2022 when the so called virus turned out to be, though deadly to some, far more benign in scope than the end-of-the-world stories told by those who had seized absolute power.

Thus it was, that the rule of law, Anglo-American jurisprudence, the American Constitution and Western democracy instantly disappeared in flurry of edicts, kangaroo courts, and declarations of absolute power by bureaucrats and politicians around the world. These self-declared all-powerful self-adoring elites acted as one, worked in unison, and moved into action simultaneously. The citizens of the West were, in one fell-swoop, transformed from free and independent citizens into political slaves and prisoners. This state of affairs continued until the Spring of 2022 when the so called virus turned out to be, though deadly to some, far more benign in scope than the end-of-the-world stories told by those who had seized absolute power. They are maintaining their rule by using social monitoring machines to track the transactions and words of every ordinary citizen in real time, every minute of every day. Any behavior or transaction that is deemed to be contrary to the dictates of the global ruling body or one of their affiliates, will be recorded by the ceaselessly operating social monitoring machine. All violations of speech and action that are vacuumed up by the machine will be permanently stored for future use. Depending on the particular country, some form of immediate punishment is meted out to the offending citizen. In Canada, most often the punishment is the freezing of their financial accounts, in the U.S. and Australia an intimidating visit by a government agent or arrest followed by a show trial is more likely.

They are maintaining their rule by using social monitoring machines to track the transactions and words of every ordinary citizen in real time, every minute of every day. Any behavior or transaction that is deemed to be contrary to the dictates of the global ruling body or one of their affiliates, will be recorded by the ceaselessly operating social monitoring machine. All violations of speech and action that are vacuumed up by the machine will be permanently stored for future use. Depending on the particular country, some form of immediate punishment is meted out to the offending citizen. In Canada, most often the punishment is the freezing of their financial accounts, in the U.S. and Australia an intimidating visit by a government agent or arrest followed by a show trial is more likely.

For the last thirty years, our politicians, the media, and the academy have been preaching the Globalism Gospel. We are being told, and continue to be told, that Globalism is great for the United States and all its citizens. All we citizens need do is sit back, not ask questions, and let the new intellectually and culturally superior Global elites lead us to their Brave New World. The truth is that Globalism, as actually practiced by these elites, has been a fraud from the beginning. Their Globalism was and is the most corrupt enterprise and the largest theft in mankind’s history. The victim of this crime is the United States of America.

For the last thirty years, our politicians, the media, and the academy have been preaching the Globalism Gospel. We are being told, and continue to be told, that Globalism is great for the United States and all its citizens. All we citizens need do is sit back, not ask questions, and let the new intellectually and culturally superior Global elites lead us to their Brave New World. The truth is that Globalism, as actually practiced by these elites, has been a fraud from the beginning. Their Globalism was and is the most corrupt enterprise and the largest theft in mankind’s history. The victim of this crime is the United States of America.

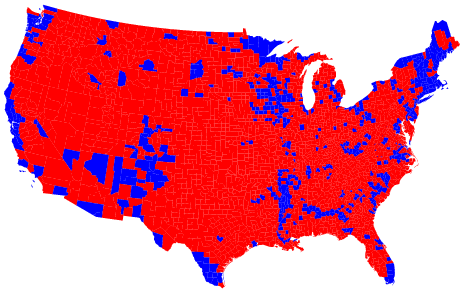

The 2016 presidential election was only partially about the personality zeitgeists surrounding Mr. Trump and Ms. Clinton. The election was, at its heart, about returning American government to its more traditional approach to governance. Donald Trump’s victory signals a giant step backward for progressivism’s long jack-booted march over America’s constitutional republic. Most of the more radical elements of the authoritarian administrative state seem to have been rejected by the American voter. Mr. Obama, while cynically and destructively going back on his campaign promise to bring Americans together and build a post racial society, did indeed keep his promise to try to radically transform America’s government and culture. The radical transformations that Barack Obama and his administration sought to force upon the country through executive orders, agency rule-making, and condescending rhetoric were, in the end, not acceptable to the majority of American people.

The 2016 presidential election was only partially about the personality zeitgeists surrounding Mr. Trump and Ms. Clinton. The election was, at its heart, about returning American government to its more traditional approach to governance. Donald Trump’s victory signals a giant step backward for progressivism’s long jack-booted march over America’s constitutional republic. Most of the more radical elements of the authoritarian administrative state seem to have been rejected by the American voter. Mr. Obama, while cynically and destructively going back on his campaign promise to bring Americans together and build a post racial society, did indeed keep his promise to try to radically transform America’s government and culture. The radical transformations that Barack Obama and his administration sought to force upon the country through executive orders, agency rule-making, and condescending rhetoric were, in the end, not acceptable to the majority of American people. The Left’s street operatives and community organizers are in full bat-swinging mode. One need merely tune into the news (except of course ABC, NBC, CNN or CBS) to see the far Left and the radical factions of the Democratic Party going after our civil society bat-blow by bat-blow. This is evidence that leads rational people to conclude that the American Left and many in the Democratic Party intend to practice insurrection and violence, not democracy. Simply take a look at the streets today and listen to the character-assassinating rhetoric of the Left for the evidence. This angry refusal to respect democracy and accept the results of the election is led and inflamed by mainstream Leftist institutions, not just by a few street thugs.

The Left’s street operatives and community organizers are in full bat-swinging mode. One need merely tune into the news (except of course ABC, NBC, CNN or CBS) to see the far Left and the radical factions of the Democratic Party going after our civil society bat-blow by bat-blow. This is evidence that leads rational people to conclude that the American Left and many in the Democratic Party intend to practice insurrection and violence, not democracy. Simply take a look at the streets today and listen to the character-assassinating rhetoric of the Left for the evidence. This angry refusal to respect democracy and accept the results of the election is led and inflamed by mainstream Leftist institutions, not just by a few street thugs. determined by the citizens themselves based on their agreements or mutual acquiescence. A society that is largely absent of politicization, i.e., a society largely absent of government enforcement of behavior, is a civil society as opposed to a statist society. When citizens cannot agree or voluntarily acquiesce they simply go their separate ways.

determined by the citizens themselves based on their agreements or mutual acquiescence. A society that is largely absent of politicization, i.e., a society largely absent of government enforcement of behavior, is a civil society as opposed to a statist society. When citizens cannot agree or voluntarily acquiesce they simply go their separate ways.